Published 03/03/2021

Bridgeman Copyright Service is honoured to administer and license the copyright of Dame Laura Knight, DBE RA RWS and Harold Knight, RA on behalf of the trustees of the two Estates.

Harold Knight RA

Harold Knight (27 January 1874 – 3 October 1961) was an English painter of portraits, especially of women, interiors, landscapes, and of genre paintings who had a distinguished and successful career, yet was overshadowed by his wife, Laura Knight (1877–1970).

Knight was born in Nottingham, England, the son of William Knight, architect, and studied at Nottingham School of Art under Wilson Foster. Nottingham had a reputation as among the best of the English provincial art schools and Knight won a series of prizes there, most notably for a series of oil studies of nudes. At the time he was considered to be the best student in the college. At the School of Art, he met fellow artist Laura Johnson, whom he married in 1903. Harold painted his future wife an early portrait in 1891. Laura later reflected that it was while sitting for this painting that she 'first got a hint that I meant as much to him as he did to me'.

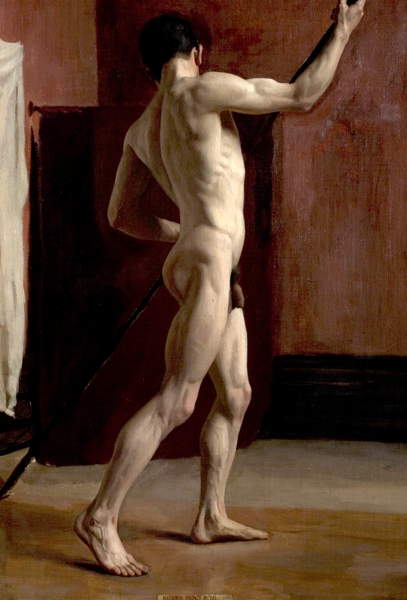

In 1896 he spent time in Paris, studying art at the progressive art school Académie Julian under Jean-Paul Laurens and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. Here he focused on drawing from a live model: an essential part of artistic training for artists during the XIX century. In these academic nude studies, models posed in a way that resembled the marble heroes of Ancient Greece allowing artists to focus on the portrayal of tensed muscles, taut contours and anatomical detail.

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries (Nottingham Castle) / Bridgeman Images

However Knight's model instead appears in a more expressive, playful and unconventional pose: there are intimacy and sensuality at play in Knight's painting, which quietly unsettles the convention of the powerful academic pose and offers up an alternative form of masculinity.

1904/1905 and 1906 Harold and his wife Laura, visited the art colony at Laren in Holland studying the Dutch masters and Harold was considerably influenced by Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch and to a certain extent by Rembrandt and Hals. This is shown in Harold’s treatments of female figures in his paintings.

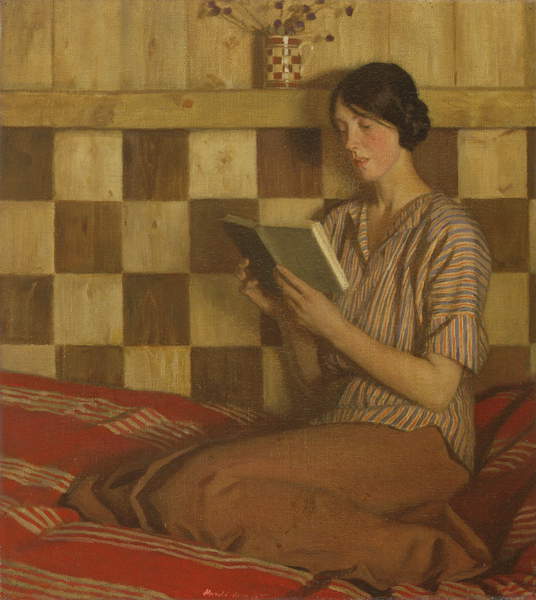

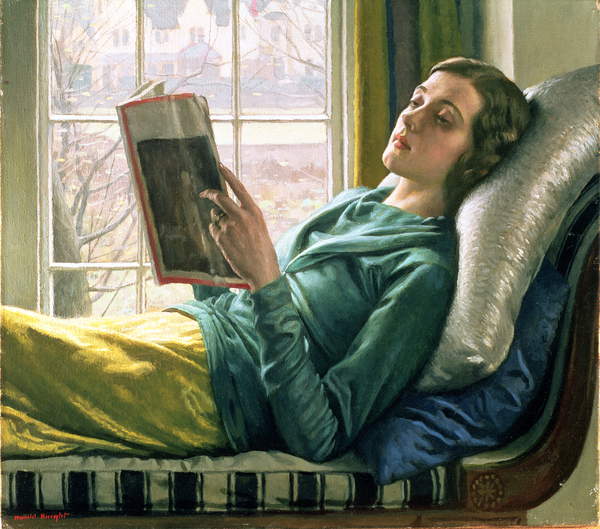

In a time when Walter Sickert and even his wife Laura were painting the female body nude, Harold Knight's fully clad female figures are seen absorbed in activities such as reading, writing and sewing in the home.

The setting of these women in domestic spaces demonstrates his interest in Dutch interior paintings. In works such as Sewing, the influence of Vermeer is evident: sunlight streams through the window to illuminate the scene and cast soft shadows on the face of a woman sewing.

Harold and Laura shared models, many of whom became close friends with the couple. Harold Knight's portrait of Ethel Bartlett from around 1935 represents one favoured sitter, the renowned English pianist. The artist has cleverly centred his composition around the musician's hands, which she clasps prominently in front of her. In another painting of Bartlett from c.1937, he portrays the pianist reclining and caught deep in thought, gazing beyond the picture frame. Once again, he has focused his attention on the pianist's hands and splayed fingers, which she wraps around her chest. Enhanced by a golden light that makes Bartlett glow, it's a sensual rather than sexual image of an introspective female figure.

Another friend that was also was a favourite model for both Harold and Laura Knight was Florence Carter-Wood, known as ‘Blote’. The story of Carter-Wood’s disastrous marriage and tragic death is well-rehearsed, becoming the subject of Jonathan Smith's novel Summer in February (1995) and the subsequent film. Munnings would frequently travel up and down to London and Suffolk after their marriage. Florence, left in Cornwall, was neglected and her friendship with a young captain in the Monmouthshire Regiment, Gilbert Evans, drew closer to the point that he realized the potential seriousness of their growing affection and decided that his only recourse was to leave England by joining a Royal Engineers Survey of Nigeria. Amid suspicions that she was pregnant by Gilbert, she took her own life on 24 July 1914. Laura Knight was called and tried unsuccessfully to revive her.

In Jean Good autobiography AJ The Life of Alfred Munnings p. 110 there is a record of Laura Knight's letters that covers a part of Florence's impossible marriage, her instability of character, her follies and refined cruelties to Munnings. (Slightly contrary to the background and character depicted in the film Summer in February).

Florence and Laura had posed for Harold’s Afternoon Tea, 1910, and among other works, she re-appears in Laura’s The Flower, 1912 and in paintings by Munnings. However, Portrait of Florence seems to be the most sympathetic rendering of the beautiful young art student in happy times as she addresses her unseen friends.

The defining tranquillity of Harold Knight's portraits, as well as showing the influence of Vermeer, point to Knight's personality: unlike his gregarious wife, the painter was known for his introverted character and gentle nature. He was also known to be somewhat subordinate to Laura, who was the one to propose. One of the couple's models and a fellow artist, Eileen Mayo, later reflected on the couple's relationship, stating that Harold was a 'good wife' to Laura.

In 1916 Knight's principles led him to be a conscientious objector: aged 43 he received his call papers. At the outbreak of the First World War, military service was compulsory for all single British men. Knight joined an absolutist minority who refused to fight; he declared himself a conscientious objector, resisting combat on the grounds of pacifism.

Conscientious objectors were required to work as labourers during the war. By this time Knight was living in Cornwall, where he and his wife had joined the Newlyn School of artists. Now, forced to work as a farm labourer on the Cornish coast, he found himself alienated by friends and colleagues, writing: 'I have lost the friendship of several people whose friendship I valued, and my career as a portrait painter has been prejudiced by my attitude towards the war I have been compelled to take.'

Knight's decision put a strain on both his physical and mental health, which didn't go unnoticed by his wife. 'Hoeing', she remarked, 'for days on end without seeing a living soul. He was again a sick man.' By 1917, Knight's health had deteriorated to such an extent that he was excused from further labour and returned to painting on a full-time basis. Throughout his life, from 1900 onwards Harold Knight was often ill, suffering badly from mouth and chest infections and later in life from arthritis. Many of Laura Knight's letters refer to Harold being ill and his having to stay in bed.

A pacifist stance is also discernible in Harold Knight's interiors from this period, in which women engage in a contemplative activity, far removed from any sort of conflict. Knight's paintings can be read as quietly subversive statements in support of his status as a conscientious objector.

When the war ended, Harold and Laura Knight moved to London, although they frequently spent summers painting in Cornwall. Despite the social ostracism, he experienced as a conscientious objector, Knight enjoyed professional success in his lifetime, exhibiting his portraits at galleries including the Royal Academy. In 1937, one year after Laura Knight was elected to the Royal Academy, Harold Knight became a Royal Academician. Between 1936 and 1945, he was also President of Nottingham Society of Artists. On the 3rd of October, he died at the Park Hotel in Colwall, Herefordshire.

Perhaps the nature of Harold Knight's personality and choices is best described by Ruth Millington, art critic and writer in her piece: Harold Knight: uncovering Britain's pacifist portraitist which has been a great inspiration for this article.

“ From the very start of his career, Knight was assertive in his personal and artistic choices: he stood by his unconventional wife, turned his male gaze on nude men and positioned his female subjects as champions of peace. A pacifist painter, Harold Knight put up a fight through his art.”

Read more about Dame Laura Knight

Sources:

http://www.damelauraknight.com/educational-information/bibliography-harold-knight/

https://artuk.org/discover/artists/knight-harold-18741961

https://artuk.org/discover/stories/harold-knight-uncovering-britains-pacifist-portraitist

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6012120